A Community of Practice

Milford Graves, Free Jazz, and the Pioneer Valley in the '90s

Gahlord Dewald :: 1/19/22 :: Mānoa, Hawai‘i

The passing away of drummer Milford Graves last year has had me thinking about his influence on the way I make sounds. Though I didn’t study with Graves, his work and practice had a meaningful influence on my own musical trajectory. Through his role in the Black Music Division at Bennington College I was able to encounter and experience free(free as in liberation) improvisation at an important time in my life. Using social learning theorist Etienne Wenger’s concepts from Community of Practice this essay sketches an example of how a community of practice shapes and changes personal trajectories.

It’s only new if you haven’t seen it yet

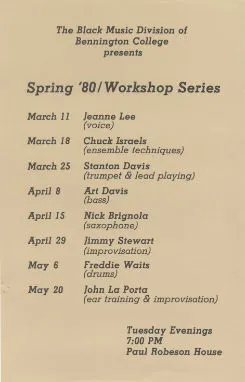

Between 1973 and 1974 Bill Dixon laid the groundwork for the Bennington College Black Music Division. This academic group would have faculty, visiting artists, workshops, performances, and public lectures which established a free jazz culture in southern Vermont. Among the founding group of instructors offering courses was Milford Graves, George Barrow, Stephen Horenstein, and Arthur Brooks. The Black Music Division provided performance, teaching, and learning opportunities for practitioners of free jazz and those seeking a wider musical experience than offered in standard “Western” music performance programs.

performances, and public lectures which established a free jazz culture in southern Vermont. Among the founding group of instructors offering courses was Milford Graves, George Barrow, Stephen Horenstein, and Arthur Brooks. The Black Music Division provided performance, teaching, and learning opportunities for practitioners of free jazz and those seeking a wider musical experience than offered in standard “Western” music performance programs.

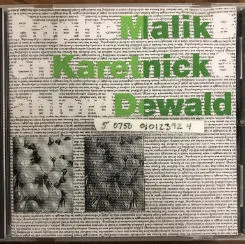

Artists-in-Residence at the Black Music Division included saxophonist Jimmy Lyons and bassist Alan Silva. Workshops, festivals, and concerts featured artists like Jeanne Lee, Chuck Israels, Marco Eneidi, Charles Gayle, William Parker, and Stanton Davis."Bennington College History: Music: 1990s," Bennington College Crossett Library, Bennington College. Retrieved 19 January 2022 Nadi Qamar taught there for many years. Raphe Malik, a veteran of the Cecil Taylor Unit,Phil Freeman, "The Unit: Cecil Taylor in 1978," Burning Ambulance, 3 Dec 2011. moved to Vermont and began teaching trumpet at Bennington in 1992. The roster of teachers peaked around ’80 or ’81 after which it whittled back down to just Dixon, Graves, and BrooksArthur Brooks' Ensemble V continues to perform throughout New England. in ’95

In 1994 there had been an academic cataclysm at Bennington College. The board and administration terminated ⅓ of the professors and eliminated tenure as a thing. Dixon and Graves both ended their teaching at the college in 1995. Among the outcomes was that many Bennington College students, no longer having access to their primary instructors, transferred out. A few of them ended up at Marlboro College near Brattleboro, where I was just arriving from the High Plains.

From the middle to the edge

In the late 90s I moved from North Dakota to southern Vermont. I was getting the hell out of the middle of nowhere. At that time I was really into Jimmie Blanton (still am, of course) and had that unnecessarily strong affinity for all things Jaco Pastorius which sometimes afflicts young men who play electric bass.

Shortly after arriving at the small liberal arts college from which I’d eventually graduate (Marlboro College, RIP), it was pretty clear there’d not be an opportunity to work on Blanton-Webster era Ellington music. And Jaco Pastorius stuff is, for the most part, a non-starter. There was a jazz quartet on campus with a solid tenor player and a good jazz electric guitarist. But it was a group of tight-knit friends and they had a bass player already. Solo bass stuff? Maybe try to start a different combo?

I was in another country.

My search for playing opportunities led to the Vermont Jazz Center’s weekly jam where Raphe Malik would frequently show up. This made for an intensely eclectic jazz jam. There’d be some usual jazz standards, some of the Latin music that is VJC’s director Eugene Uman’s forte, and some free blowing led by Malik and some of his friends. I was the only bassist who showed up regularly and so I was able to put in a lot of hours on jazz charted and uncharted.

It was at one of these sessions where I met a recently-former Bennington College student, a trumpeter who had stayed in the area to work with Raphe. He and I would get together to play music. He also helped bring me up to speed on free improvisation by recommending books and recordings and sharing things he’d learned in the time he’d been at Bennington College.

Between the Bennington College refugees and interacting with the free jazz component of the VJC sessions I learned about a music series further south at the Unitarian Universalist Meeting House in Amherst. This opened up an entirely new opportunity to see some great live shows.

Participation

Through all of these different interactionsa) Playing at the VJC jam sessions with Raphe Malik and from there being invited to perform in other settings. b) Hanging out and talking about free jazz performers, books, and recordings. c) Attending free jazz shows I began to get a sense of how working this way felt, how to make these sounds, how to listen for sounds that emanate instead of analyze instructions for sound, how to re-sense music and sound together.

In Communities of Practice, Etienne Wenger notes two complementary elements that are important for a social group that learns together. We’ll get to the second in a moment, but the first important element is participation.Etienne Wenger. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity (University of Cambridge Press, 1998), p55 Actively participating with the people, concepts, and materials that make up the effort of the social group. This includes the work itself and also the conversations about the work.

Having direct and regular access to a master musician in a loosely structured, extra-curricular way, unconcerned with grades or other academia—as I was able to do with Raphe Malik at the jazz jams and at other social events in which he invited me to perform—was transformational in what I do with music. Learning directly how to “rehearse” with a free improvisation group, to negotiate and navigate roles and expected outcomes and attitudes continues to inform my ensemble and solo work.

to negotiate and navigate roles and expected outcomes and attitudes continues to inform my ensemble and solo work.

Having a guide, in the form of the former Bennington College student, to show me the ropes of how things worked helped me become a competent participant in making freely improvised music. There was a tremendous amount of history and culture related to free jazz that I did not yet know. Having someone who was willing to spend the time to get me up to speed improved my access to performance opportunities.

The opportunity to experiment, learn, and ultimately make these sounds was an important part of becoming competent as an improvisor. I was becoming a different player, a different thinker, and perceiving the world differently as a result.

Thingification

The second core element in Wenger’s community of practice is reification, which is mostly a fancy way of saying “take a mental concept and make it a thing—a physical thing or a gestural/performance thing, doesn’t matter just make it a thing.” A social group transforms and encodes their participation into things.Etienne Wenger. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity (University of Cambridge Press, 1998), p57 Those things then go on to become the focus of further participation.

The books and recordings recommended by the Bennington grad were a reification of previous performances and documents of the conversations of others along the way. Attending free jazz shows by performers like Matthew Shipp, Hamid Drake, and William Parker, allowed me to see how performances worked and were received. All of these kinds of things were ways that I learned to share direct experiences with others.

Knowing specific recordings or performers over the years has served as a kind of shibboleth in conversation of “You’re into jazz, cool, what kind of jazz are you into?” My musical development has taken a more specific path as a result of experiencing and engaging with these “things”—books, recordings, shows. These reifications helped me assemble meaning out of the experience of making music in this community of artists.

Communities of Practice extend outward

As I noted at the outset of this article, I never studied with Milford Graves but he had an impact on who I am as a musician. By helping to establish a center of learning at the Black Music Division of Bennington College he attracted musicians and students who then disseminated his style of thinking and playing and enquiry out to the other side of the Green Mountains where I had recently arrived. Those musicians and students then created further opportunities to participate in the conversation.

The Black Music Division at Bennington College was an important element in the sonic geography for southern Vermont. Without the establishment of this community of practice it’s unlikely that I would have encountered free jazz at the moment when I needed an artistic outlet that was flexible enough for my circumstances. I’m sure I’d be making music, but I’m grateful that I got pulled into this way of experiencing sound. I’m grateful for the people and friendships I’ve made. I’m grateful for being able to interpret and feel the moment, to collaborate with respect and without structure.

Jake Meginsky Jake Meginsky performing on a series curated by Greg Davis at the Champlain College Art Gallery, Burlington, Vermont studied with Milford Graves and has reified, in collaboration with cinematographer Neil Young, Graves' philosophies into a film, Full Mantis. It's a beautiful work of cinema: thoroughly engaging in visual, auditory, and musical ways. Watching it reminded me of all the different ways that Graves' concepts and approach filtered over the Green Mountains and into the ways I began to make music in my mid-20s.

Jake Meginsky performing on a series curated by Greg Davis at the Champlain College Art Gallery, Burlington, Vermont studied with Milford Graves and has reified, in collaboration with cinematographer Neil Young, Graves' philosophies into a film, Full Mantis. It's a beautiful work of cinema: thoroughly engaging in visual, auditory, and musical ways. Watching it reminded me of all the different ways that Graves' concepts and approach filtered over the Green Mountains and into the ways I began to make music in my mid-20s.

This documentary ensures that Graves, the Black Music Division, and the free jazz community of practice that was assembled in that corner New England continues to expand and grow. I am grateful to have been able to play a small role in helping the film come into the world and further the cycle of participation in this way of experiencing music.